Study participant Emerald Darbyshire with LJMU researcher Benjamin Buckley. Photo by James Facey.

Researchers are trialling a new exercise referral scheme that could revolutionise the way doctors prescribe physical activity. The study, led by the UK’s Liverpool John Moores University, invites patients to reflect on the reasons behind their inactive lifestyles and come up with their own solutions, supported by regular meetings with a trained exercise instructor.

‘Prescriptions for exercise’ have been given for decades in many countries, with varying results. Frequently doctors have found that simply advising non-active patients to exercise is not enough to get them to change their behaviour. The authors of the new study hope that their approach – piloted in early 2017 with promising results – will provide a more effective solution that can be adopted by health services worldwide, to provide a lifetime saving on medical costs for successful participants.

Dr Paula Watson, senior lecturer in Exercise and Health Psychology at LJMU’s Physical Activity Exchange, said: “We are trying to do it the hard way, but the way it should have been done 20 or 30 years ago. In the UK a lot of this has been rolled out without any evidence base. One of the issues we have here is that when GPs refer to these schemes, they don’t know if they’re successful or not because they never hear anything back about how their patients have got on.”

Thirty-three patients with inactivity-related health complaints are taking part in the study. A further 19 are following a standard exercise referral scheme, and there are 16 in a control group. Dr Watson said that, in a world first for an exercise referral scheme, the methods were designed by a group of stakeholders including public health commissioners, patients, exercise referral practitioners, a doctor and a fitness centre manager, to foster autonomous motivation. “We want them, by the end of the scheme, to want to do exercise for their own personal reasons and to keep it up,” she explained.

“The instructors ask the clients questions about why they’ve come to the scheme, any issues they might have had in the past, any concerns they’ve got, and anything they think might get in the way of being able to exercise – to identify barriers and help them come up with solutions to overcome those. There’s a lot of open questioning and getting to know the client.” She said traditional exercise referral schemes had often focussed on showing people how to use gym equipment. “They weren’t learning anything about the client’s motivations, barriers and the psycho-social side. It wasn’t about those behaviour changes.”

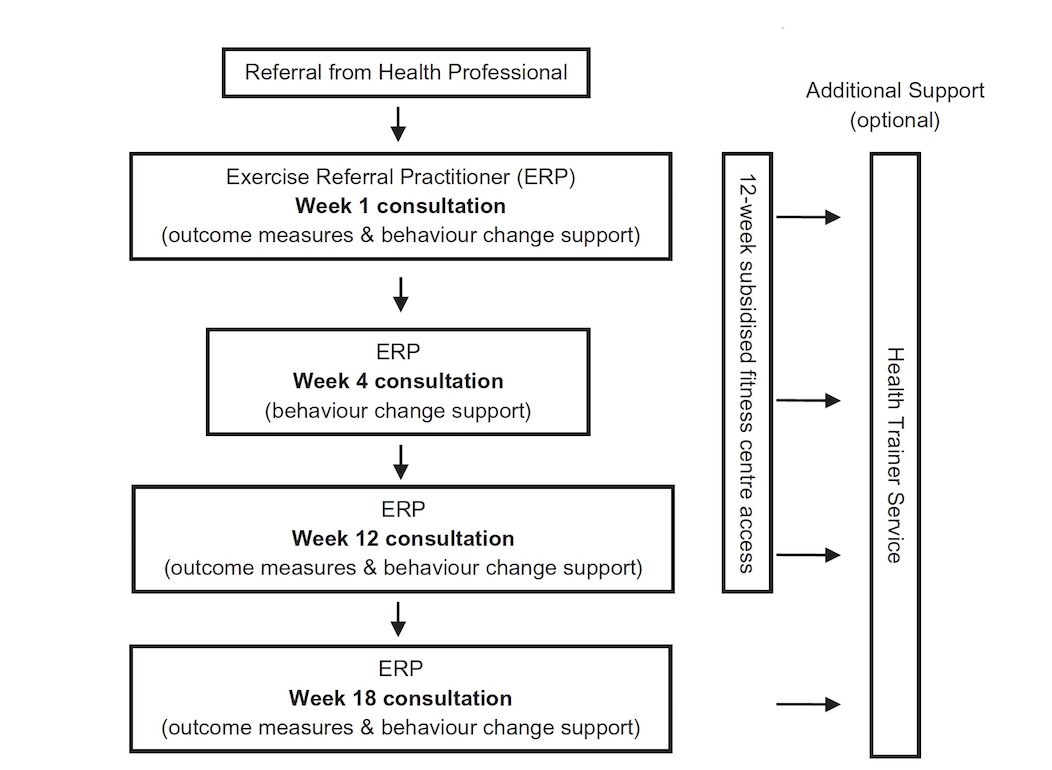

A diagram showing how the trial exercise referral scheme works. Patients meet with a trained exercise referral practitioner in weeks 1, 4, 8, 12 and 18 to review progress and set personalised action plans. They also have subsidised fitness centre access for 12 weeks, and optional guidance from a health trainer to address issues such as nutrition, smoking and alcohol.

The co-development paper for the trial noted that some previous studies of exercise referral schemes have indicated that they are not effective. However, Dr Watson warned that the schemes themselves have not always been evidence-based, and often failed to collect long term outcome data – so in fact the results are unclear. “I’d hate to see them decommissioned because there’s a real opportunity to reach the people most in need. What we need to be doing is look at how can we make these schemes better so they can become effective, rather than getting rid of them. And this is where multidisciplinary working is so important. What I’ve seen from the commissioning world is that they’ve got a limited amount of funds, they have to spend this within set timescales, and this leaves little time to invest in the kind of work that we’re doing, as it takes time, patience and effort to work together with people to change the status quo.”

“Despite the National Quality Assurance Framework advocating that exercise referral schemes (ERSs) should go beyond advice-giving, recommending exercise, or offering patients vouchers to attend exercise facilities, the majority of UK ERSs continue to offer 12–16-week exercise prescriptions and few exercise referral practitioners are trained to provide behaviour change support. Consequently, exercise referral requires a cultural shift to align physical activity provision with World Health Organization guidance and consideration needs to be given to behaviour change training and education for ERS providers.”*

The study involves researchers from the universities of Bath and Gloucestershire in the UK, Brock University in Canada, and Radboud University, The Netherlands. LJMU has funded two PhD researchers to carry out the project, while working closely with local commissioners, managers and practitioners in Liverpool, where the trial is taking place. These students will ensure that the model can be applied in the real world, and examine the costs of the intervention compared with the lifetime health costs of inactive behaviour. Non-communicable diseases, many of which can be prevented by an active lifestyle, are responsible for 71% of deaths. This year Liverpool is hoping to be certified as a Global Active City by the Active Well-being Initiative (AWI), in recognition of its work to motivate and empower residents to be more active.

PhD researcher Benjamin Buckley said: “Even ten minutes of regular physical activity can dramatically reduce someone’s chances of developing diabetes, heart disease and high cholesterol. In fact, the greatest public health benefits are realised when we move from being inactive to a little bit of activity.” The results of the main study are expected to be published in 2019. Follow the progress of the research by signing up to the AWI newsletter.

Governments and health providers interested in carrying out research in exercise referral, or behavioural change training for local practitioners, can email Dr Watson.

Trial participant Emerald Darbyshire (left) with Exercise For Health Instructor Juliette Norman. Photo by James Facey.

“I feel way better in myself physically and mentally.”

Emerald Darbyshire, 64, described how she had had an active job as a teacher, but since retirement has done little physical activity, apart from walking the dog. “I’ve never been in a gym before in my life, never done exercise since I left school. I’ve realised how much more walking you can put into your life, and I’ve enjoyed that as well. If it’s a ten-minute trip now, I always walk unless I’ve got something heavy to carry. I like that as much as exercising in the gym or at the swimming pool.”

Originally referred to the scheme with high cholesterol, she added: “Even if it hasn’t gone down, I feel that the whole thing has been very positive. I just feel so much fitter. I’ve lost a small amount of weight, I’ve lost centimetres off my waist. I think you just feel better in yourself. The only thing I found intimidating was taking that first step to go and do exercise.

“I feel way better in myself physically and mentally. I’ve loved doing the exercise. I think the coaches have been superb because they haven’t made you feel guilty when you haven’t done as much as you would expect to do. They’ve been very encouraging and giving you small goals that you can achieve, and then gradually extended it.”

Another participant, a 58-year-old woman, said before starting the scheme she had muscle loss and depression which prevented her from exercising. A month in, she has started going to the gym, takes group classes in Zumba and low circuit training, and is about to start swimming. “It gets you out of the house and gives you a purpose,” she explained. “It builds up your strength. Being with people builds me up a lot.” She said the exercise had helped increase her confidence to the point where she was about to start a voluntary job, as a step towards seeking paid employment.

Juliette Norman, Exercise For Health Instructor, said: “I’d say around 80 percent of people have completely changed their lives by increasing their activity, and most carry on after the 18 weeks. We used to have an hour-long induction with each new member regardless of their reason for referral, but then we often wouldn’t see them again. We had no follow ups and the activity was solely gym or pool focused which isn’t always appropriate. Subsequently, retention rate was probably about 25%.

“The way the scheme is run now is much more personable, flexible and is focused on what the member wants to do. They don’t have to rely on the gym for activity. The regular monthly reviews mean we are able to offer consistent support and build a good relationship with each person which means people come back. If they don’t turn up after four weeks, we phone them quite a few times. We don’t have many that we haven’t been able to get hold of since the induction.”

She explained that during the induction process, they discuss how increasing their physical activity levels will benefit the participant’s health and well-being. Together, they come up with a plan that will fit with their lifestyle including setting weekly and monthly goals. “The focus is not about using the gym but increasing daily physical activity for life. Some plans do not even include the gym at all, or we incorporate it after the first four or eight weeks.”

At the end of the 12 weeks, the GP referral gym membership comes to an end but members are supported for another six weeks and they are able to join as a regular off peak member. Miss Norman said about 75 percent of people take up the offer. Leisure centre staff are trying to publicise the scheme as far as possible to get referrals, by making links with local doctors and hospitals and doing various outreach events.